IN THE BEGINNING

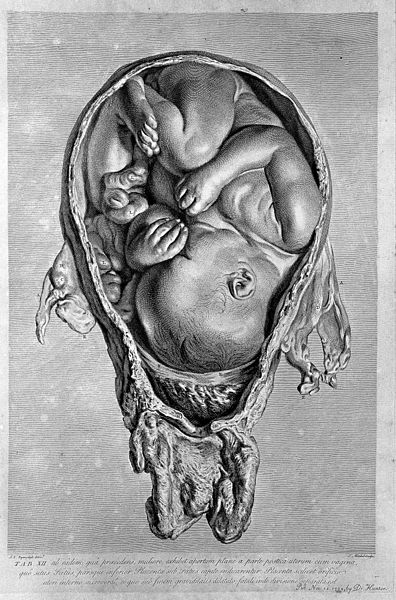

Let’s go to the beginning. Everyone of us started out as the product of the fusion of a sperm (from our father) and an egg (from our mother) and grew and developed to become a fetus that was birthed after about 9 months. The uterus of our mother was our home, for those 9 months.

Let us consider a girl, beginning from the moment she is born and follow her through her teen years and on to menopause, outlining a general picture of her reproductive life. She starts her life on earth fully loaded with thousands of eggs in a structure called an ovary. She also has a uterus. The eggs will stay quiet in her ovary as she grows and matures into a toddler and through childhood.

Then, something remarkable happens at the phase of life called puberty; there is a distinct hormonal change in the girl, the result of which is the development of her body into a state that is capable of procreation.

At puberty, the girl’s uterus starts to form a new thick layer that includes lots of new blood vessels. From her collection of thousands of eggs, one egg (from now on, and more or less every month) outgrows all other eggs and this specialized egg is capable of joining a sperm to develop into a new offspring. If a sperm fuses with her specialized egg, the new layer of her uterus that is thickened and has many new blood vessels will be their source of nourishment.

If there is no fusion of the egg and sperm, the thickened layer of the uterus and new blood vessels are shed. Menstruation is the natural shedding of the layer of the uterus that is deemed unnecessary as there is no developing fetus in the uterus. Menses is the technical term that refers to the shed layer of the uterus, i.e. the dark red drops of blood and uterine tissue that gently drip out of the her body once a month.

Within the next month or so, her body will build a new layer of the uterus in preparation for nourishment of a fused sperm and egg. This cycle of building and shedding of the layer of the uterus begins in her early teen years (this is true for most girls) and continues until menopause, and is interrupted by a developing baby.

This article explores how the first menstruation and subsequent menses were viewed by traditional Kenyan societies. It also describes current views, practices and policies on the management of menses.

THE PAST

A study by M G Gathigia and co-authors published in the book Linguistic Taboo Revisited: Novel Insights from Cognitive Perspectives (excerpts of which can be found here) looked at the various ways that one Kenyan tribe (the Kikuyu) refers to menstruation. Gathigia’s team grouped the metaphors used to indicate one is menstruating as follows (example of metaphor and English translation): those referring to i) a period in time (e.g. kahinda ka mweri – a period in the month), ii) its red color (e.g. thakame ya muiru – dark red blood), iii) a visitor (e.g. mugeni– visitor) and iv) a disease (e.g. kuruara – to be sick).

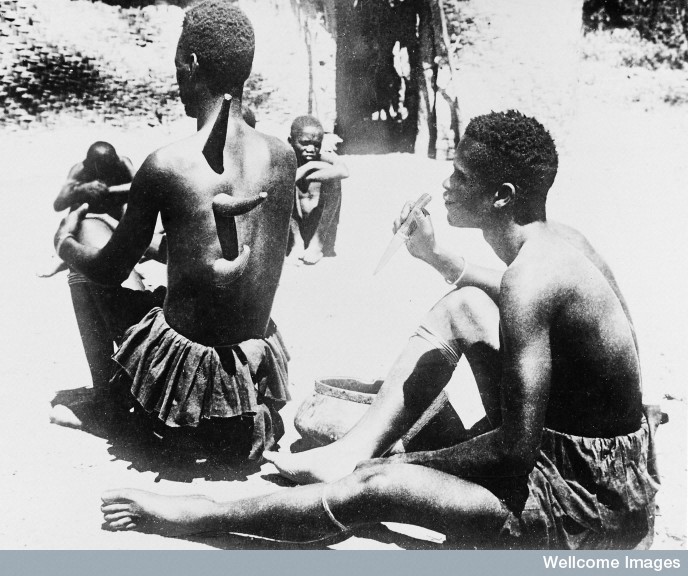

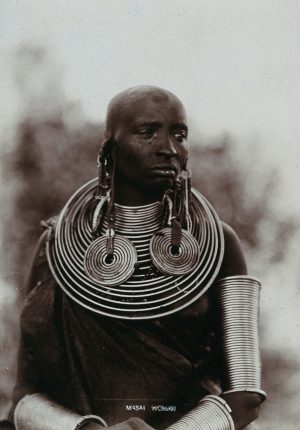

Gathigia and his co-authors also discussed metaphors that illustrate menstruation as a symbol of fertility. They gave the example of the first menses as being referred to as kuraga ikenye which means to break an egg, a phrase indicating the transition from childhood to female maturity. In the essay by J.S. La Fontaine Ritualization of women’s life crises in Bugisu, (excerpts of which can be found here), she describes the tradition of marking a Gisu’s [Gusii’s] girl’s first menstruation by the girl receiving a gift and having to make visits to relatives. The girl’s uncle is also tasked with offering a sacrifice to the ancestors and laying up a meal (for his niece) that is fit for an important guest. The girl returns to her village marriageable and an asset to her father.

There are reports on traditional Kenyan societies imposing restrictions on what persons that were menstruating could or couldn’t do. In J S La Fontaine’s work on the Gusii (cited above), once a person started menstruating, they were prevented from eating chicken or eggs lest they become barren.

In 1922, C W Hobley, a provincial commissioner in the colonial government, published the book Bantu beliefs and magic (which can be found here) where he describes the Kikuyu, in the early part of the 20th century, as a society that viewed a person menstruating as one to be avoided. On page 122, he writes the following of the Kikuyu beliefs:

If a person touches menstrual blood, he or she is thahu [cursed]; or if a man cohabits with a woman in this condition he is thahu. The person who is contaminated will first take some cow dung and then red ochreous earth … and plaster it on the part of the body touched by the blood; ochre is said to be used because it is the same colour as the blood; the woman from whom the contamination came is also thahu. The mundu mugo [medicine man] has to be called in to purify the persons.

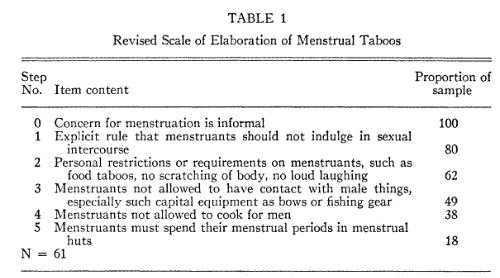

According to an article by L S B Leakey published in 1930 and available here, the Maasai seemed to put few if any restrictions on people who were menstruating, other than that they should not have sexual relations while menstruating. This type of restriction was fairly common among different societies across the world as is shown in the mid 1960s publication by F W Young and A A Bacdayan titled Menstrual taboos and social rigidity which can be read here. In this work, they produced a scale that attempted to grade the levels of restrictions placed on menstruating persons by their society. It is reproduced below. (The Maasai were part of the study by F W Young and A A Bacdayan, and as highlighted above, they fell at level 1 of the scale.)

The reasons for the restrictions imposed upon persons who are menstruating have been explored by several authors, including F W Young and A A Bacdayan (in the work cited above) and they viewed the menstrual taboos as a method used by men to suppress women. However, in the book Blood Magic: the anthropology of menstruation, (excerpts of which can be read here), the editors T Buckley and A Gottlieb caution against lumping all menstrual practices together as geared to suppressing women. They suggest that one views the practices with the lens of the culture from which they are drawn and in doing so, one may find additional (not contradictory) conclusions to Young and Bacdayan e.g. menstrual practices give women access to gender exclusive ritual powers and enhancing female solidarity.

THE PRESENT

How much has life changed for girls and women since the days described in the studies above? One has got to feel for the girls in schools interviewed for a report by McMahon and her co-authors and published in 2011 when they describe how they feel when they are menstruating with words like:

shame, fear, distraction, confusion and powerlessness

In the same report by McMahon’s group, one of the girls’ teachers said:

I know why she is distracted. This is something (teachers) know… when the session ends, she will not leave the room (until she is the last to leave) and then when she leaves, she will wrap sweaters around her middle and she will say, ‘Teacher I am so sick’ and then she will go from school and not come back all day or many days.

About a year ago, (I write this article in August 2018), a video was published that contrasts the lives of those who can walk into a supermarket in the capital city of Kenya, Nairobi, and be inundated by choices on what to use to manage their menses while others in one of the arid parts of Kenya called Daaba still struggle with less than adequate methods. Here is the video.

Period poverty is a term used to describe the state of struggle to get the products one needs to manage one’s menstruation due to a financial handicap. Period poverty is not a problem that is unique to Kenya. In August 2018, an article highlighting period poverty in the UK was published in the Guardian.

There has been tremendous progress at the government policy level in tackling the obstacles that girls and women face as they manage menstruation in Kenya. The government of Kenya’s Finance Act of 2004 repealed value added tax on sanitary towels and tampons. Then, in 2011, the government of Kenya’s budget, read by then finance minister Uhuru Kenyatta, allocated money for the purchase of sanitary towels for primary school going girls. The minister’s speech read:

Hon. Members, we all need to appreciate when we educate a girl child we in turn educate the whole society. For this reason, we must do everything within our powers to ensure that girls are facilitated to attend schooling throughout the month just like boys. Through this budget, we are responding to their basic needs by allocating Ksh.300 million under the Ministry of Education to provide sanitary towels to all needy primary school going girls. This is a token to demonstrate we are a caring Government. I urge other organizations, including non-governmental organizations to complement this noble initiative.

The Basic Education (Amendment) Act No. 17 of 2017 went a step further. The government of Kenya set itself the obligation of providing means of managing the menstruation of girls pursuing a basic education. This Amendment Act says that the government will:

provide free, sufficient and quality sanitary towels to every girl child registered and enrolled in a public basic education institution who has reached puberty and provide a safe and environmentally sound mechanism for disposal of the sanitary towels.

It is clear that the government appreciates that ensuring that girls do not miss school because they are menstruating is one of its key obligations. These girls are being given the opportunity to secure a future where they can be able to self-manage their menses.

This government project of giving out menstruation management products is not perfect and is evolving, as is evidenced by the recent change in the ministry that receives the project’s funds – from the Education ministry to the Gender ministry. A girl in a school where free sanitary pads are offered will still have to forgo privacy in order to receive the government’s help; the thought of me at age 13 signing paperwork for my supply of pads (as the girls in this county have to do) makes me cringe. However, there is no doubting the noble motive behind the project.

Non governmental organizations have also stepped in to meet the needs of girls and women who are dealing with period poverty. To explore more on their work, see what Zana Africa (who work in Kenya) and No more taboo (who work in the UK) are doing.

THE FUTURE

Let us all work towards the day when when all girls and women have the means to provide for themselves the products they need to manage menstruation.