The early years

The first Christian missionaries arrived in Kenya in the late 19th century. Ann Beck’s well renowned book, A history of the British Medical Administration of East Africa, 1900-1950 which was published in 1970 (hereafter referred to as Ann Beck’s book) states that the missionaries perceived

…the gospel of healing as an essential aspect of their work among the Africans.

It wasn’t easy for missionaries to set up in Kenya. Robert Strayer, in the review article Mission history in Africa: new perspectives on an encounter published in 1976, tells the story of how the arrival of the first resident missionary to the Taita in 1883 coincided with a period of famine and drought. The missionary was seen as the cause of these calamities and was quickly expelled from the community. After this, missionaries were not allowed in the Taita community for almost a decade.

Some communities had a different interpretation (from that of the Taita) of their circumstances. For example in the Taveta community, in situations where traditional medicine failed to remedy sickness or natural calamities, Robert Strayer observed more receptivity to Christianity.

From Ann Beck’s book, we learn of how desperate the situation in Kenya must have been. For example, many lives were lost in the outbreaks of the plague in Nairobi in 1902, 1905, 1906, 1911, 1912 and 1913 and in Mombasa in 1913. Ann Beck’s book describes the appearance of indigenous Kenyans afflicted by yaws (a bacterial infection affecting the skin, bone and cartilage) by writing that they:

… showed an appalling amount of physical incapacity…

Some of the other diseases and conditions in Kenya in the early part of the 20th century that the missionaries were dealing with were malaria, small pox, malnutrition and leprosy. The missionaries were not always successful in meeting the expectations of the indigenous Kenyans. Some conditions had no cure (for example, cancer or sterility in the 1910s or 1920s). Sometimes, there were just no answers to the problems of life. This was met with disappointment by the indigenous Kenyans.

Missionaries under the colonialists

Although the missionaries had arrived before the colonialists, once the colonial government was in place, the missionaries operated under the colonial government’s political and economic power. However, at the beginning of the 20th century and up until the late 1910s, the missionaries were the sole providers of ‘European’ health care to the Africans. In Ann Beck’s book, we read:

After the Europeans had been taken care of, the administration could concern itself with the health of the Indians who were needed for the building of the railroad and for the promotion of trade. The African contingent of the population, used to tropical climates, need not be a concern of the medical administration except in emergencies. Beside, government officials knew that the various missions could take care of them; or even if they could not do so, the administration accepted this kind of wishful thinking.

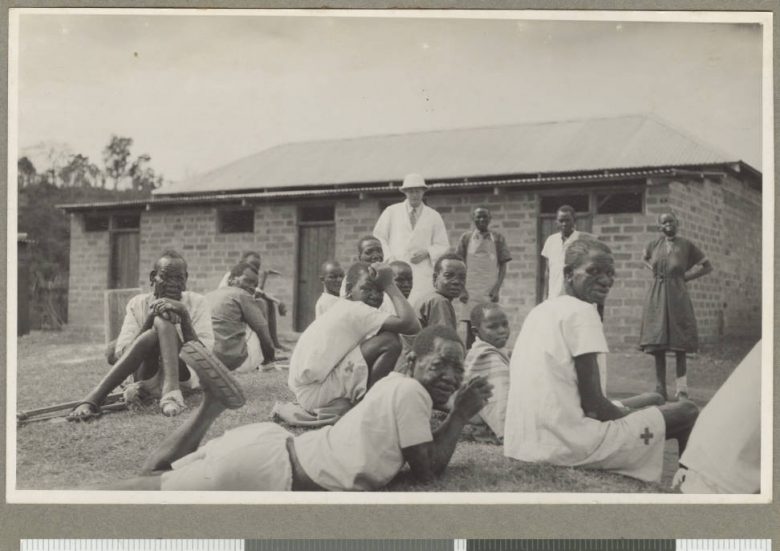

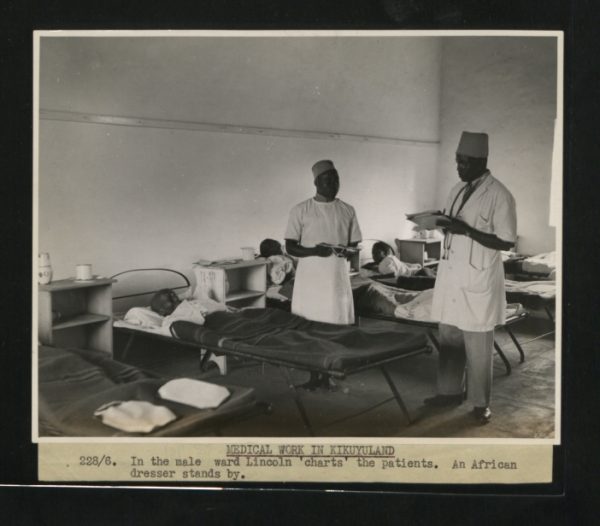

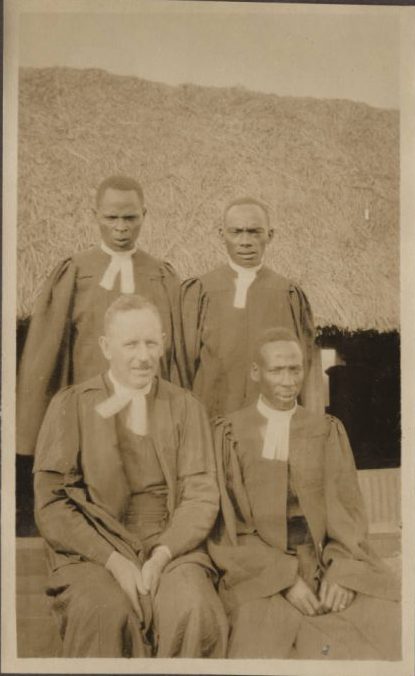

The Church of Scotland Missions (CSM) began the Kikuyu Medical Mission in 1907 under Dr. John W. Arthur. He was the surgeon, the specialist and the general practitioner. Ann Beck’s book describes Dr. Arthur as a humanitarian and a pro-African who strongly supported and facilitated the medical training of indigenous Kenyans.

In the 1920s, the colonial government’s approach began to change and the government began to offer health care to the indigenous Kenyans. (Please see my article here on health during the colonial period).

While government health facilities expanded slowly due to limited funds for ‘proper’ medical doctors and nurses, missions had less rigid recruitment policies. Some missions like the White Fathers and Mill Hill Mission didn’t have trained doctors but instead had a missionary layman dispensing medicine, dressing wounds and diagnosing minor ailments.

Although the colonial government felt that some missions did not meet the standards of the London College of Physicians and Surgeons, they were content to have these missions continue their work because they were not yet in a position to establish healthcare facilities for the indigenous Kenyans. The government subsidised the missions by offering grants. Also, with the shortage of medical personnel for the Kenyans, the government funded the training of Kenyans at the medical missions.

Later on, the colonial government started to become concerned that the missions offering healthcare were stealing the limelight from government. Anne Beck quotes Dr. Gilks who was the Prinicipal Medical Officer in 1921 who said:

A government hospital is a tangible sign of government activities…but it is doubtful whether a subsidized mission hospital is in any way connected in the minds of the majority of the patients as being anything more than a token of benevolence of the missionaries.

Missionaries taking sides

The missionaries had a varied and often complex relationship with the colonial government. Charles M Good describes how the missions facilitated colonialism in his article Pioneer Medical Missions in Colonial Africa published in 1991. He says:

Early mission stations, together with their out-stations, were at once part of the larger political network of the imperial state (the earliest missions often acted in lieu of or as proxy for state authority) and a microcosm of the whole apparatus.

Although the missionaries received funds from their home bases in Europe and America, as noted earlier, the missionaries also received colonial government grants to run their health services.

A different side of the missionaries is reported by Charles Hartwig in his article Church-state relations in Kenya: Health issues [1] published in 1979. He writes:

…they [the missionaries] were often seen by the Administration as spokesmen for the Africans, serving as African “representatives” in the Legislative Council, for example.

Ann Beck also reports how the missionaries defended Christian interests. She reports how Dr. Arthur of Kikuyu Medical Mission strongly campaigned against forced African labour sanctioned by a labour circular in 1919.

The issue of female circumcision (the procedure that is now known as female genital mutilation (FGM)) was a contentious one during the colonial period. FGM had been a part of the culture and tradition of several indigenous communities of Kenya and the community leaders wanted to preserve this custom. Dr. Arthur was firmly against FGM and actively campaigned against it. Other missionaries, on the contrary, did not speak out against FGM to avoid loss of converts. Robert Strayer writes in his article Mission history in Africa: new perspectives on an encounter:

Anglican unwillingness to push the initiation issue beyond a certain point resulted in far fewer defections from the stations of the Church Missionary Society than from those of its Presbyterian and American fundamentalist rivals.

It is worth pointing out that the colonial government also chose to keep a low profile on this issue of FGM. Ann Beck’s book includes a quote of J. Pease, senior commissioner of Kikuyu Province in 1929 who said:

I consider the general policy of government towards female circumcision should be one of masterly inactivity

An established presence in Kenya

By the middle of the 20th century, the Christian missions in Kenya were part and parcel of the medical services of the county. Their close cooperation with the government continued throughout the colonial period. On independence, they continued to work with the Government of Kenya. While Christian missionaries have been the focus of this article, faith-based organisations of affiliations other than Christianity also play an important role in providing health services in modern day Kenya.