In the beginning

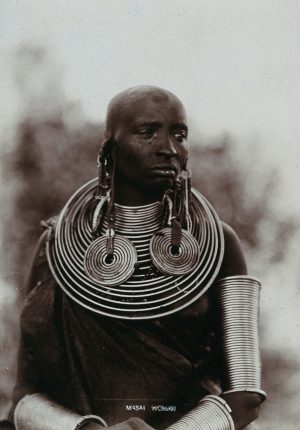

Traditional medicine was practised in Kenya long before the missionaries and colonialists set foot in Kenya and has been passed on from generation to generation. There is a lot of interest in the huge variety of plant-based preparations used as traditional medicines and in the healing practices undertaken by Kenyan communities. Several published reports on them are available online, and here are examples from the Kikuyu, the Nandi, the Maasai and the Samburu.

This article will focus on traditional medicine in the modern Kenya, although it is worth bearing in mind that medicine has been and still is very pluralistic in Kenya. For example, healing may be sought from modern health facilities, while at the same time believing that the origin of the poor health is spiritual and therefore relying on spiritual practices like prayers and/or traditional healing practices.

Elliot Fratkin documented this in his work titled Traditional medicine and concepts of healing among Samburu pastoralists of Kenya, which was based on studies conducted in the 1970s to 1990s. He wrote:

Although much of Samburu medicine is based on a practical knowledge of anatomy and plant behavior, it would be wrong to imply that Samburu healing is simply empirical or pragmatic and thus categorically distinct from religious beliefs and ritual practices. Although many of their healing techniques have visible effects, Samburu healing is predicated on the belief that many illnesses including those brought about “by God alone” or due to the immoral actions of sorcerers lead to internal pollution and decay, a belief that is ultimately spiritual.

Who uses traditional health care?

Traditional medicine is still used today to treat different kinds of ailments. In Gabriel Kigen and his colleagues’ article Current trends of Traditional Herbal Medicine Practice in Kenya: A review published in 2013, they reported that traditional herbal medicines are used mainly by those struggling to meet the costs of modern medicine and/or with poor access to modern health facilities. They also indicated that traditional medicines are mainly used by people living in rural areas.

That said, people living in urban areas also use traditional medicine. In a study carried out in 2012 by Mothupi MC titled Use of herbal medicine during pregnancy among women with access to public healthcare in Nairobi, Kenya: a cross-sectional survey, about 12% of 333 mothers with a baby not older than 9 months old, reported having used [traditional] herbal medicine during their pregnancy.

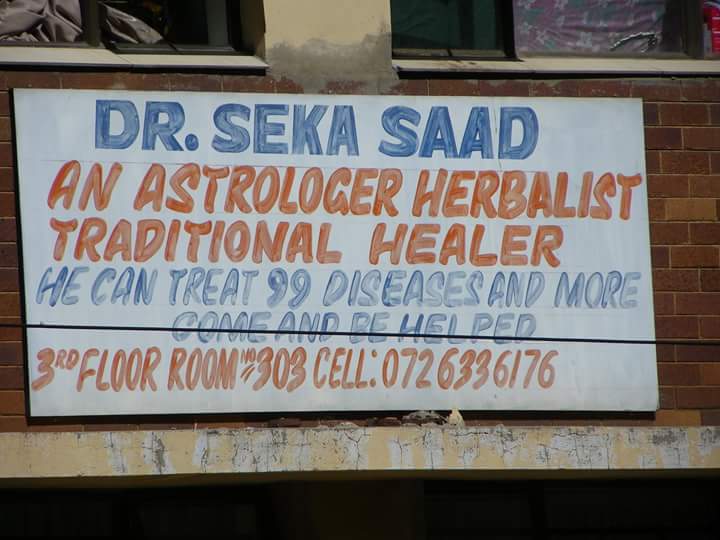

Who provides traditional health care?

Mothupi MC’s report indicates that some mothers self-prescribed [traditional] herbal medicine. It is implied that they obtained the knowledge on what to use from family or friends.

John Lambert and his colleagues in a report titled The Contribution of Traditional Herbal Medicine

Practitioners to Kenyan Health Care Delivery, published in 2011 for the Government of Kenya, interviewed 258 (112 female and 156 male) traditional herbal medical practitioners from five provinces of Kenya. The practitioners each identified their specialisation as herbalist or generalist or dentist or traditional birth attendant or bone setter or spiritual/faith healer. (Some practitioners had more than one specialty.)

All 258 traditional practitioners in John Lambert’s study viewed their skills as God-given. Most of them had been apprentices of relatives or other traditional herbal medical practitioners. It seems that providing traditional medicine does not make their ends meet as all traditional practitioners interviewed supplemented their income by undertaking other non-herbalist activities like farming or business. These traditional practitioners reported catering to mainly low income clientele.

Is traditional medicine beneficial?

The report Traditional medicine and concepts of healing among Samburu pastoralists of Kenya by Elliot Fratkin portrays traditional medicine rather favourably. Elliot Fratkin says:

Samburu herbal medicines are not placebos whose value is mainly symbolic, but effective purgatives, astringents, and analgesics based on their particular chemical constituents.

Elliot Fratkin gives the example of a plant of the Cassia species known in Samburu as senetoi which is used for symptoms of malaria. Sentoi contains quinone. (For many years, the active ingredient quinone was used in modern medicine for the treatment of malaria).

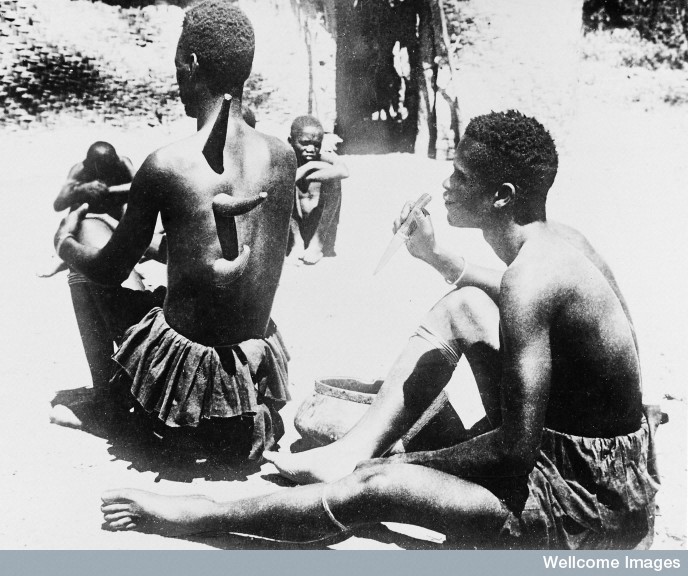

Another facet of traditional medicine that is reported to have a beneficial effect is the currently fashionable practice of cupping. Cupping is an ancient practice that involves applying a cup on the skin and creating a vacuum. It has been used to treat a variety of ailments across the world.

The marks of cupping have been spotted on celebrities including Olympic swimming champion Michael Phelps.

FUN FACT: Those circles are the end product of an ancient healing technique called cupping. #Rio2016 pic.twitter.com/BsP1PPjqBQ

— NBC Olympics (@NBCOlympics) August 8, 2016

The BBC article here reported other celebrities who are attesting to the benefits of cupping.

Does traditional medicine cause harm?

John Lambert’s report The Contribution of Traditional Herbal Medicine Practitioners to Kenyan Health Care Delivery suggests that clients are keenly aware of the abilities of their traditional medicine practitioners. Indeed, they seek modern medical treatment for conditions they consider serious. Here is how John Lambert’s report puts it:

That these healers do not treat dangerous conditions should come as no surprise to those who understand the economics of their situation: healers who live in the same community as their patients would not survive in business if they failed to cure patients. The impact would be far more serious if patients were likely to die because a practitioner failed to cure them. Thus, it is not surprising that healers do not specialize in illnesses in which we do not expect them to have any particular skill.

However, things do go wrong in traditional medicine. For example, traditional birth attendants are a key target of the government of Kenya and international agencies in the efforts to improve the health and indeed save the lives of expectant mothers and their babies.

Traditional birth attendants are involved in a large number of births in Kenya as, according to World Bank data from 2014, only about about 61% of all births in Kenya were attended by skilled health staff i.e. health staff in formal health facilities. Targeting traditional birth attendants is therefore absolutely vital in reducing the dismal 510 deaths of women for every 100 000 live births in Kenya that occurred in 2015 (World Bank data). (I discuss how this targeting happens in the article here)

What is the policy in Kenya on traditional medicine?

There are obviously huge gaps in scientific knowledge on the effectiveness of traditional medicines. However, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the government of Kenya have seen the need to take on board the aspects of traditional medicine that are beneficial.

International policy

With this in mind, WHO has come up with the following definition of traditional medicine:

It is the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness.

[My emphasis in bold.]

The WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023 seeks to help member states of the WHO (like Kenya), in developing proactive policies and implementing action plans in traditional medicine. This includes promoting safe and effective use of traditional medicine.

Traditional medicine is a new territory for both WHO and the governments of its member states. By 2023, WHO hopes to have developed and updated WHO technical documents and tools, organised training workshops and facilitated information sharing.

Government of Kenya policy

The important Health Act, 2016 of the government of Kenya unified all the existing health related laws of Kenya. Clause 74 of the Health Act mimicked WHO’s traditional medicine strategy, indicating that polices will be established to guide the practice of traditional medicine in Kenya.

This Health Act established regulation of the practice of traditional medicine, including standardising practices, controlling the levies charged and setting up mechanisms for referrals from traditional practitioners to modern health facilities.

The government and WHO’s efforts to make traditional medicine part of the mainstream health services is a bold step. It places value on the skills and knowledge passed through the generations and will help preserve them for future generations.