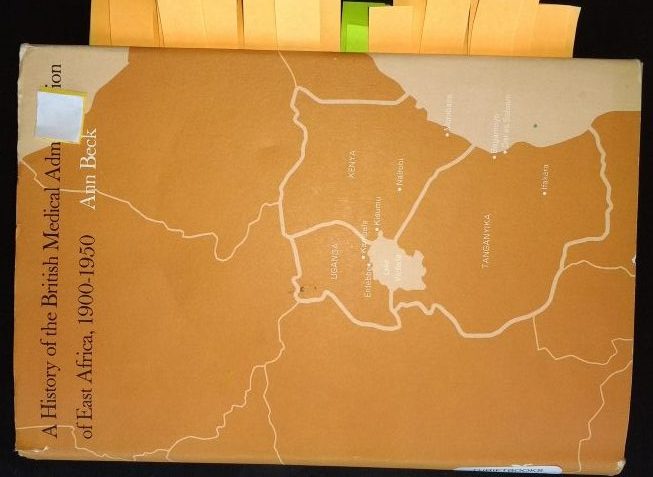

Ann Beck’s book A history of the British Medical Administration of East Africa, 1900-1950, which was published in 1970, tells the story of health and medicine in Kenya during the colonial period. (I cite this book in this article and hereafter, refer to it as Ann Beck’s book).

The beginning

The story begins when the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC) was set up in 1888 to conduct trade in what is present day Kenya and Uganda. IBEAC’s job was ultimately, to develop, administer and exert influence over this part of Africa. IBEAC had a medical services unit, which included doctors, that took care of its employees. In 1893, it was clear that IBEAC could not achieve its objectives and it handed over its operations to the UK government.

The UK government assumed responsibility for East Africa and IBEAC’s medical services unit became the responsibility of the UK Foreign Office. Dr. R. U. Moffat, who had been a doctor for IBEAC, became the first Principal Medical Officer (PMO) of the combined Colonial Medical Services of East Africa.

The London School of Tropical Medicine, which opened in 1899, was established to offer specialised training for medical officers before embarking on a career in the Colonial Medical Service. The colonial Medical Officer (MO) would be working in a colony to fulfil the objectives of the British government which saw medical colonisation as a springboard for political colonisation. Ann Beck quotes the British Medical Journal of 1905 which stated that ‘the lancet is more powerful than the sword’.

Not for the indigenous people

The first colonial medical services were geared towards the Europeans and were only concerned with the indigenous Kenyans when epidemics struck. Ann Beck wrote in her book:

After the Europeans had been taken care of, the administration could concern itself with the health of the Indians who were needed for the building of the railroad and for the promotion of trade. The African contingent of the population, used to tropical climates, need not be a concern of the medical administration except in emergencies. Beside, government officials knew that the various missions could take care of them; or even if they could not do so, the administration accepted this kind of wishful thinking.

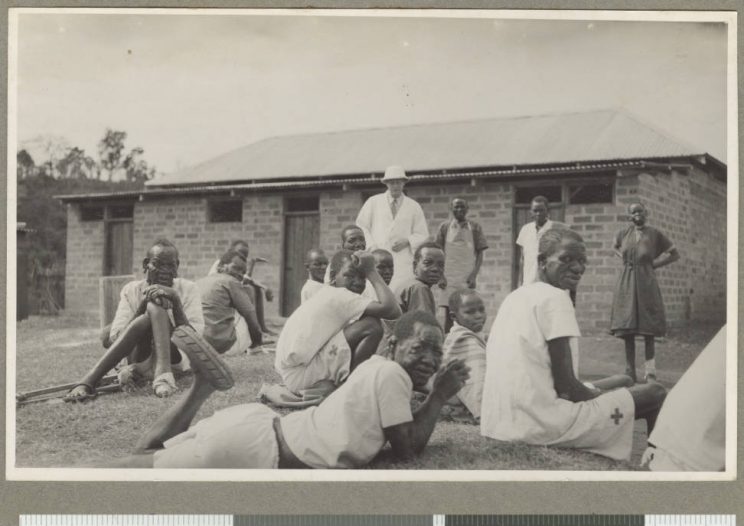

As mentioned in the above quotation, the mission hospitals played a big role in providing healthcare for indigenous Kenyans during the colonial period. (I explore the role of the missions in healthcare in my article here. Indigenous Kenyans, also, still continued to seek traditional medicine during the colonial period, a topic which I discuss in the article here.)

The complacency of the colonial government with regard to the health of indigenous Kenyans, along with the famine and epidemics of the 1910s, caused devastating loss of lives of indigenous Kenyans. The 1918-1919 report of one Provincial Commissioner of Kenya, Harry Russell Tate, documents the plight of indigenous Kenyans and the effect of loss of indigenous peoples’ lives on the colonial government. His words are recorded on page 208 and 209 of the PhD thesis of T H R Cashmore titled Studies in district administration in the East Africa Protectorate (1895-1918) by which can be found here. Harry Russell Tate said:

The past disregard of the medical needs of the Reserve have cost us the lives of several thousand bread winners and the loss to Government incidentally of thousands of rupees in taxes.

and

…failure to safeguard the health, working conditions, and legitimate rights and aspirations of the native population is a policy of sacrificing the future for the needs of the present, and can only end in our ultimate exposure as unjust stewards and in the fate reserved for those who are adjudged unworthy of their trust

Improving indigenous peoples’ health

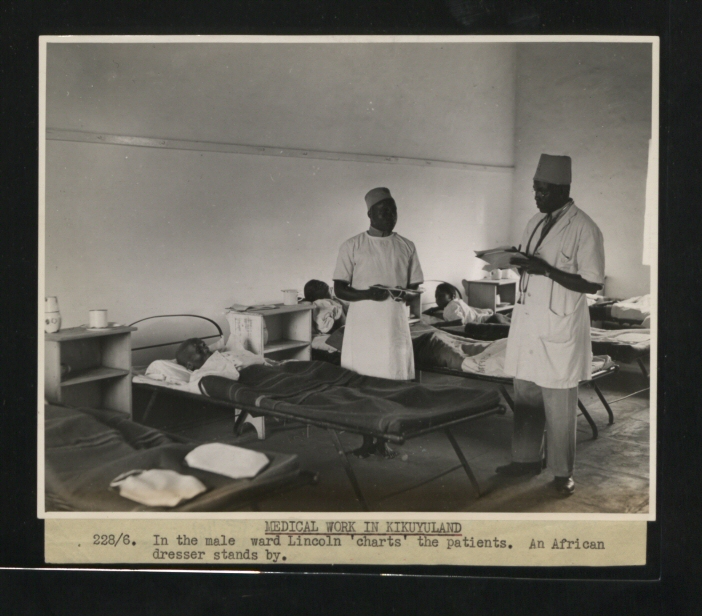

In the 1920s, Ann Beck’s book narrates how the approach of the colonial government began to change as they sought to improve medical care for the indigenous Kenyans. They set up dispensaries for the indigenous Kenyans, staffed by indigenous Kenyans. Dispensaries offered inpatient and outpatient facilities and were led by an indigenous Kenyan known officially as a ‘medical resident assistant’ who was trained in ‘technical medical work’.

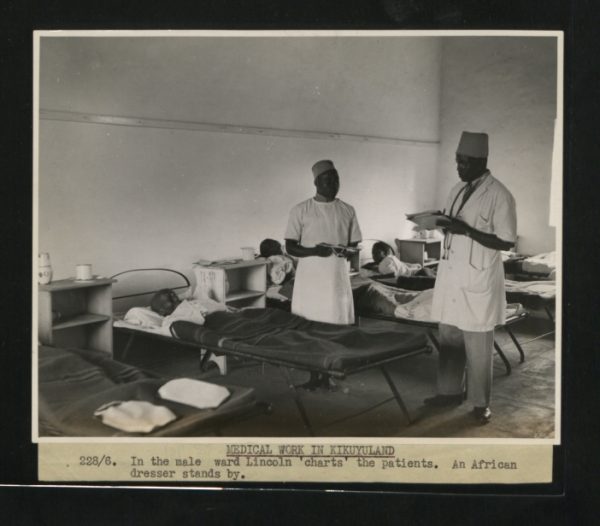

Dispensaries also had a traditional dresser and a rural medical dispenser. Ann Beck’s book states that after three months of training in a government hospital, the role of a traditional dresser was that of a dresser of ulcers and wounds. A graduate dispenser had undergone a three year course and was expected to conduct the out-patient clinic, refer serious cases to the senior officer, keep records, undertake clinical side-room laboratory work and dispense stock mixtures. A European Medical Officer (MO) would make regular scheduled visits to the dispensaries.

Ann Beck’s book documents how the colonial government’s medical expenditure per year was below or about £200,000 in the 1920s and 1930s but it started to rise significantly in the mid-1940s and by 1948, the government was spending about £590 000 in Kenya. She writes that this was because in the mid-1940s, the colonial government’s ambition to provide health care for the indigenous Kenyans increased as they unveiled plans to establish health centres throughout the colony, create a new and larger medical training school and complete the building of the ‘African hospital’ in Nairobi.

Dr. J S Kennedy charted the history of this African hospital in Nairobi in his paper The Glasgow-Nairobi Link 1965-67 published in 1968. He notes that the ‘African hospital’ started out as the Native Civil Hospital in the 1940s. Ann Beck’s book reports that six operating theaters and 300 more beds were added to the hospital in 1950. In 1951, Dr. Kennedy then notes that this hospital was opened as The King George VI hospital. (This hospital was renamed Kenyatta National Hospital after independence.)

Apart from The King George VI hospital, there were other ‘native hospitals’ serving the indigenous Kenyans. ‘European’ medicine steadily became popular during the colonial period.

Although there were considerations to charge for health care throughout the colonial period, medical services were offered for free, financed by local taxes. Ann Beck reported that one of the colonial government officials, Dr. R. R. Scott, summed up the reason why free medical services were offered to Africans in East Africa as:

Medical services represented the chief benefits which the peoples of East Africa had been led to expect in return for taxation.

It is also important to note that the colonial government placed emphasis on preventative rather than curative measures. Their policies were geared towards measures like improving sanitation, providing health education and immunisation programmes.

So did the health of indigenous Kenyans improve or decline or stagnate during the colonial period? This is a challenging question to answer, not least because health is such a complex phenomenon to measure and the colonial period is one plagued with a scarcity of data and records. In addition, one cannot dispute the inhumane treatment of indigenous Kenyans during the colonial period and the negative effect that had on indigenous Kenyans’ general well-being.

However, Alexander Moradi sought to answer this difficult question in a study published in 2008 titled Towards an objective account of nutrition and health in colonial Kenya: a study of stature in African army recruits and civilians, 1880-1980 which can be read here. He based his study on the fact that the height of individuals in a population indicates how well the basic human needs, including nutrition and healthcare of the population, are being met.

Alexander Moradi’s study showed an overall increase in height of indigenous Kenyans from the majority of communities sampled in the 20th century during the colonial period. This indicates that, in general, the health and nutrition status of the indigenous Kenyans improved during the colonial period. Here is how he describes and interprets his other findings:

Firstly, large regional inequalities existed in late 19th and early 20th century Kenya. Nutritional status was exceptionally poor in the central region [of Kenya], whereas conditions around Lake Victoria and in pastoral zones were much more favourable.

Secondly, the nutritional status of cohorts born in the 20 years prior and after colonisation did not change significantly. Therefore, accounts of pre-colonial sufficiency, often implicitly made, cannot be maintained.

Thirdly, from 1920 onwards secular improvements [in health] took place which continued after independence over the first 15 years of independence.

Fourthly, this development was particularly dynamic in the central region [of Kenya], so that inequality between ethnic groups [from central Kenya, Lake Victoria and pastoralists] declined over the course of the 20th century.

Of course there are many questions following on from Alexander Moradi’s work. The one question that will remain unanswered is whether the height and nutrition status of the population would have improved or declined or stagnated had there been no colonisation.