The problem

There were few African doctors working in East Africa during the colonial period. In 1958, one of them, Samson Nathan Mwathi, at a conference in San Francisco, USA, gave a talk titled Medical Problems in Kenya (which can be read here). Highlighting one of the problems, he said:

We need many more African doctors. At present we have less than 25 qualified in the University College of Makerere in Uganda.

During the colonial period, East Africa’s African doctors were trained at the medical school at Makerere University College, Uganda. When Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania became independent, they formed a federal university, University of East Africa. The federal university had three constituents: Makerere University College, University college of Nairobi in Kenya and University College in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania.

Although the federal university enhanced the cohesion of the three newly independent nations, the lack of a medical school based in Kenya and owned by Kenya was a major problem for the newly formed government of Kenya. Ann Beck, in the book Medicine, tradition and development in Kenya and Tanzania, 1920-1970, published in 1981, notes that at Kenya’s independence in 1963, there were mass resignations of the expatriate staff, (which one can assume included doctors who had served in the Colonial Medical Services). Trained health personnel were therefore in short supply at independence.

The vision

The man who would kick-start the process of getting Kenya its own medical school was Dr. Njoroge Mungai. Njoroge Mungai was born in 1926 and after high school, he left Kenya for South Africa, without a passport (as the colonial authorities would not give him one). After his studies in South Africa, he was enrolled in a university in London but left London on gaining a scholarship to study in at Stanford University in the USA. He went on to earn a medical degree from Stanford University in 1957 and he is featured on their alumni pages here.

Dr. Njoroge Mungai returned to Kenya and became the secretary to the political party Kenya Africa National Union when it was launched in 1960. On independence, in 1963, he became the Minister of Health. In his role as the new Minister of Health, Dr. Mungai saw the setting up of a medical school in Kenya as one of uttermost importance. He approached foreign medical schools to help him realise this objective.

The helpers

The University of Glasgow heeded the Minister of Health’s call. Dr. J S Kennedy became the clinician in charge of the first contingent of Glasgow expatriates who came to Kenya. He describes the role his team played in setting up the medical school in Nairobi in an article published by the Scottish Medical Journal in 1968 titled The Glasgow-Nairobi Link 1965-67.

Dr. J. S. Kennedy’s article narrates how, between 1965-1967, 45 expatriates from Glasgow hospitals and the University of Glasgow moved to Nairobi to establish the medical school. With the teaching and administration staff in place, there was an agreement with Makerere University College that some of their medical students, on a voluntary basis, would undertake a term of clinical training in Nairobi. Often, more students (of Kenyan, Ugandan and Tanzanian nationalities) than could be taken, volunteered to move to Nairobi.

A senior medical coordinator was needed to oversee the developing medical school and initially, this role was taken up by Sir Charles Illingworth of Glasgow. He was followed by Professor Gordon King, retired dean of the Faculty of Medicine in Perth, Western Australia.

The curriculum and more helpers

The curriculum of the medical school at Nairobi was divided into two years of ‘pre-clinical studies’ which would take place at Chiromo campus (where units like anatomy and biochemistry were studied) and three years of ‘clinical studies’ based at Kenyatta National Hospital.

The intriguing story of how the teaching staff in Anatomy got ready for the new intake of medical students in Nairobi is narrated in Dr. Joseph’s Mungai’s autobiography, From Simple to Complex: The Journey of a Herdsboy, snippets of which are published here. Dr. Joseph Mungai, a newly recruited senior lecturer in Anatomy, describes how he made the journey from Nairobi to Kampala to secure human bodies for dissection by the medical students. He then had to drive the borrowed land rover that carried the ten human bodies donated by Makerere University, back to Nairobi, passing via the manned Kenya-Uganda border post. He arrived in time for the opening of the medical school.

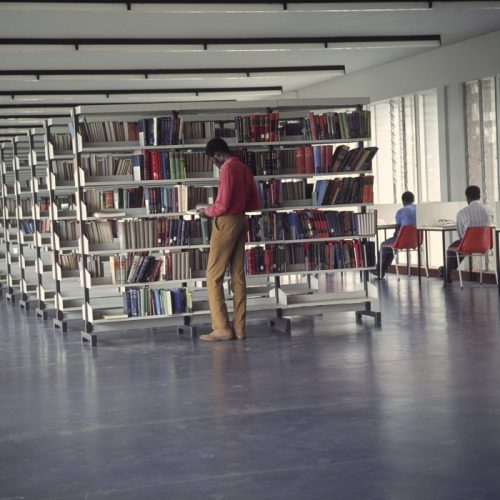

There were other key players in setting up the medical school. Dr. Kennedy’s article notes that the development of the pre-clinical units was paid for by the Kenyan government and the German Catholic organisation Misereor. The UK Loans Fund provided £65000 to purchase equipment and grants of £500 for the purchase of books was arranged by the British High Commission. Funds to set up the medical school were also obtained from donations from commercial firms in the UK. The Wellcome Research library was availed for use by the students.

Professor WFM Fulton, in his inaugural lecture at the University of Nairobi in 1971 titled Towards the end of the beginning: development, implications and prospects of Kenya’s medical school (which can be read here), acknowledged the help of staff from the University of Podova, Italy, in establishing the pre-clinical units of anatomy and biochemistry.

Dr. Kennedy’s article also demonstrates the key role the Government of Kenya played in availing the infrastructure needed for the medical school. This included a hospital (Kenyatta National Hospital), a medical research laboratory and premises for lectures, common rooms, student accommodation and offices.

Its own medical students and more helpers

The Board of the Faculty of Medicine was formed in June 1967 and in July 1967, 26 students began the first year of medical training at the medical school in Nairobi.

In 1968, the Canadian government sponsored McGill University to provide clinical specialist teaching personnel for the medicine and paediatric units.

Eva Rathgeber, who for many years was based in Kenya working for the Canadian government’s research funding organization International Development Research Centre (IDRC), researched the influence of expatriates on the Kenyan medical education. In an article published in 1985 which can be read here, Rathgeber reports that during the period of Canadian sponsorship (1968-1973), 39 McGill expatriates had worked in Kenya and 11 Kenyan doctors had attended postgraduate training at McGill.

In 1974, Professor Douglas Cameron, professor of medicine at McGill University published an article on the role the Canadian expatriates played in setting up the medical school in Nairobi, which can be read here. At the end of the article, he states:

Having had the opportunity of serving Canada in this way has been a source of satisfaction to McGill. It is our considered opinion that the project has been an eminently successful and worthwhile effort of which all Canadians can be proud. In the event that the Government of Canada decides to continue medical teaching aid to Kenya after 1974, McGill stands ready again to undertake the operational role.

Graduates of a Kenyan medical school

The first batch of medical graduates trained entirely in Nairobi graduated in 1972. Professor WFM Fulton’s inaugural lecture given in December 1971, a few months before these students graduated, reviewed the journey travelled in setting up the medical school in Nairobi and the challenges that needed to be overcome to ensure its success. He said:

A fine medical school has been founded, it now needs to be secured. This will not happen until the young men of Kenya take up the challenge with the approval and positive backing of their seniors and prepare themselves to continue the building of something of lasting value.

…

The next phase will call for the utmost effort, if the standards already set are to be maintained. These standards are not only of technique and scholarship but of ethical integrity, scientific honesty and hard work. Standards do not just survive, they must be cared for.

…

It will not be long before most of the professional teachers who have laboured to set up this medical school have gone. The baton will be passed to other runners in this complex relay.

The legacy

Many of the people involved in setting up the first medical school in Kenya are now retired or have passed away. Dr. Njoroge Mungai passed away in 2014. A few months before he died, he gave the interview below where you can hear him tell this story of the first medical school in his own words. (Begin watching from 6 minutes in up till the 13 minute point.)

Dr. Njoroge Mungai had a funeral befitting the hero he was. The President of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, was one of the pall-bearers at his funeral.

Rest in Peace Dr. Magana Njoroge Mungai. You will be greatly missed. pic.twitter.com/rPjKXcaQnx

— Uhuru Kenyatta (@UKenyatta) August 26, 2014

It is my hope that this article makes us aware of the huge investment that has been made to set up the first medical school in Kenya. More importantly, I hope it will show that success is possible where there is vision, commitment and goodwill. The first medical school in Kenya has brought about a lasting positive change on the lives of Kenyans and beyond. All Kenyans and their helpers should be immensely proud of what they achieved and seek to continue the work started by the pioneers I have described in this article.