One of the groups of indigenous people who live in the north of Kenya, the Turkana, call the large, stunning, green lake Anam Ka’alakol, meaning “the sea of many fish”. Lake Turkana is an important resource, in particular, for the people of the north of Kenya. (For more on the culture and heritage found in the north of Kenya, see my other post.)

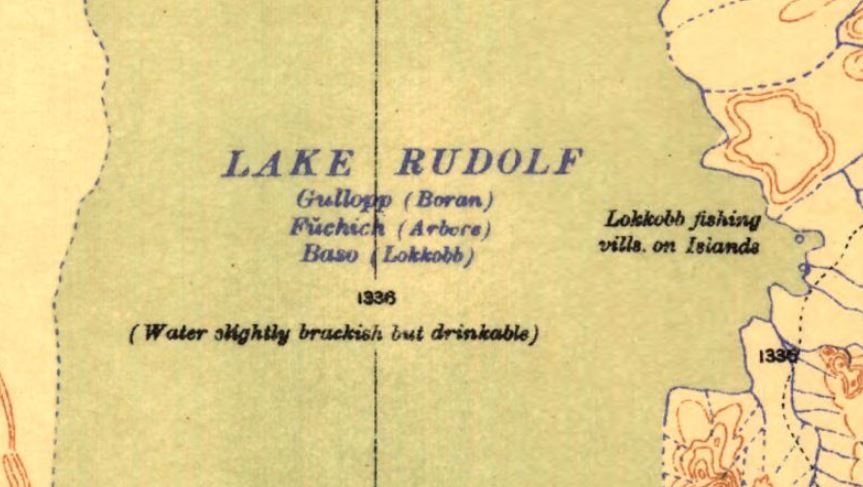

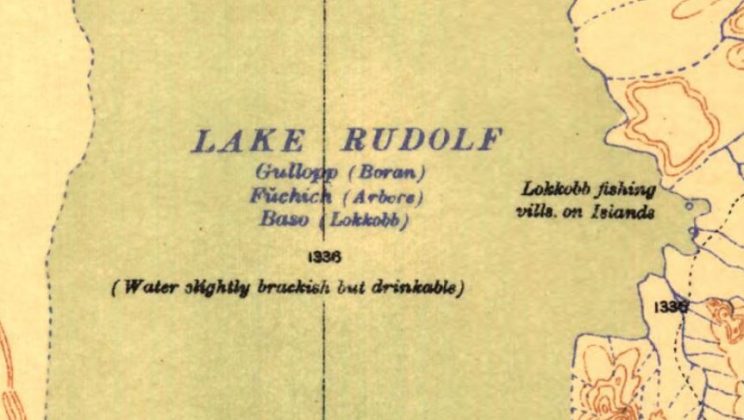

The map below, published in 1909, which can be viewed in its entirety here, describes fishing in the waters of Lake Turkana (then known as Lake Rudolf). Although, the waters are described as ‘slightly brackish but drinkable’ in 1909, today, Lake Turkana’s waters are considered unfit for human consumption.

1909 map describing the taste of the water and fishing activity at Lake Turkana (then known as Lake Rudolf).

The high fluoride levels in the waters of Lake Turkana are now known to cause health problems including staining of teeth and bone deformities. People, therefore, rely on wells or natural springs in this arid part of Kenya. Unfortunately, when these alternative water sources dry up, people and livestock drink the waters of Lake Turkana.

Even with brackish waters, Lake Turkana, has impressive ecological and wildlife diversity including fish, crocodiles and birds. The short National Geographic video below captures the one-of-a-kind home of flamingos – a crater lake found within Lake Turkana.

Lake Turkana is fed by three rivers: Rivers Omo, Turkwell and Keiro. It has no outlet. Its waters evaporate, leaving water that is rich in salts.

River Omo contributes more than 80% of the water of Lake Turkana. River Omo is found entirely in Ethiopia, originating in the Ethiopian Shewan highlands.

Ethiopia is enthusiastic about building dams, and River Omo has a series of dams; the third one is called the Gibe III. Gibe III was started in 2006. It was built by the Italian construction company Salini Costruttori SpA. Salini’s promotional video, (found below), of the more or less completed Gibe III, gives one an idea of the sheer size of this project.

Jon Abbink, a professor of African ethnic studies in an Amsterdam university, who conducts research in Ethiopia, published an article in 2012 that, in my view, offers a balanced view on Gibe III. He reports that Gibe III was set to generate 1870 MW of electricity. Ethiopia consumes very little electricity (about 580 MW in 2008) but sees the dam as an opportunity to develop the country. Jon quotes a speech given by Prime Minister Meles Zenawi during the 13th Annual Pastoralists’ Day celebrations in 2011 on page 124 of the article:

We are determined to speed up our development in an environmentally-friendly way. We want our people to have a modern life and we won’t allow our people to be a case study of ancient living for scientists and researchers.

By all accounts, a modern life requires access to electricity. Data from the World Bank indicate that only about 27% of Ethiopians had access to electricity in 2014; Kenya had 36% of its population with access in the same year.

The same World Bank data also shows that Ethiopia generates more electricity than Kenya. It is no wonder that Jon’s article notes that the Kenyan government signed a memorandum of understanding with the Ethiopian government agreeing to the dam and will purchase some of the excess electricity generated by Gibe III, to supplement its growing needs.

So why was Gibe III a controversial build? Several media publications (including The Economist), non-governmental organisations and Jon’s article reported that The World Bank and the European Investment Bank refused to fund Gibe III directly.

The Economist article summarized the views of the critics of Gibe III as follows: they are concerned that the regulation of flow of the Omo River by the Gibe III would have significant detrimental consequences.

More specifically, critics predict the loss of the natural annual flood of the River Omo that sustains crops; there was no flood in 2015 and the one of 2016 was inadequate. They also note the forceful resettlement of pastoralists in Ethiopia. In Kenya, critics warn of the loss of Lake Turkana as water is diverted for irrigation of sugar cane in Ethiopia.

It was down to the readers of this article in The Economist to offer the positives of Gibe III in the comments section of the article. They observed that this project will provide the much needed energy for development of this region of Africa, as the Prime Minister said in the speech quoted above.

One commentator mused that there will now be controlled irrigation as opposed to uncontrolled flooding. Another reader noted that Gibe III is a renewable energy source, which is good for the planet.

So, who funded Gibe III? According to Jon Abbink’s article, Gibe III was built by the Ethiopian government with the help of the African Development Bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and the Italian government (because the dam was being built by an Italian company). By 2010, Gibe III had already cost over 2 billion US dollars.

Gibe III was inaugurated on December 17th, 2016 by Ethiopia’s prime minister, Hailemariam Desalegne. Now that the dam is operational, what can we expect?

A 686km power line, the ‘Eastern Africa Interconnector’ is being built to connect Kenya’s power grid to this source of electricity.

Will the levels of water in Lake Turkana change with regulation of the flow of River Omo? What will be the impact on the ecology, and in particular, the wildlife and the fisheries of Lake Turkana, if water is diverted for irrigation?

This story of the dam and the lake remains unfinished. Please see my post on UNESCO’s request for preservation of the heritage in the north of Kenya in the age of Gibe III.