The Turkana Basin (also called the Lake Turkana basin) traverses the western part of the Kenya-Ethiopia border. It is known for its impressive fossil deposits.

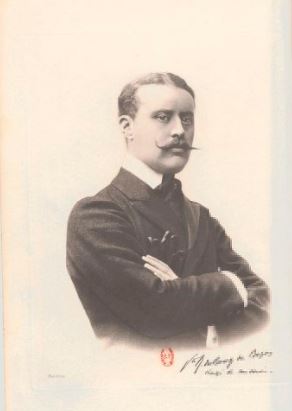

In 1902-3, the French aristocrat, le Vicomte Robert du Bourg de Bozas led an expedition that found and collected mammalian remains at the north end of Lake Turkana. He wrote about his expedition in a French book published in 1906 which is available here.

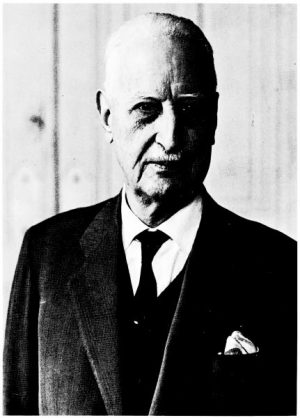

In 1932-3, another French expedition led by the Algerian-French Camille Arambourg was undertaken in the north end of Lake Turkana. He, too, carried away many fossil bones back to Paris, though no hominid fossils (predecessors of today’s humans) were found in that expedition.

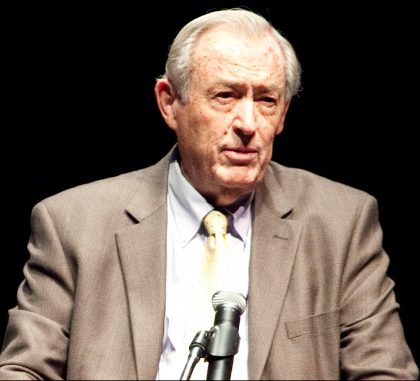

Years passed and then in the late 1960s, an international, disharmonious group set up in the Turkana basin. The exploits, successes and failures of this group are relayed in the engaging book on fossil hunting in the Turkana basin by the American paleontologist Jon E. Kalb, Adventures in the Bone Trade: The Race to Discover Human Ancestors Afar Depression, published in 2001 by Copernicus Books, New York.

Jon, who also had the opportunity to set up and lead his own successful expeditions in the Turkana Basin in the 1970s, and therefore knows what he is talking about, writes that the 1960s international group in the Turkana Basin was actually three competing parties.

There was a Kenyan contingent, led by an ailing Louis Leakey and his son, Richard Leakey. The French party was led by the now elderly Camille Arambourg, with the help of Yves Coppens and an American crew was directed by F Clark Howell.

Each party was searching for individual fame in this fossil rich area. Fame would would come to the group that found the first hominid fossils, and the older the fossil, the better.

The Kenyan contingent found the first hominid, a largely complete skull and skeleton specimen about 130 000 years old. The French then found a hominid jaw which was about 2 million years old.

Jon writes that Richard Leakey, realising his team had been assigned the ‘youngest’ site, moved the Kenyan contingent to study an area to the east of Lake Turkana called Koobi Fora. This move proved to be very fortuitous as here, they found many more hominid fossils that led to Richard Leakey’s lasting international fame, and the envy of his colleagues.

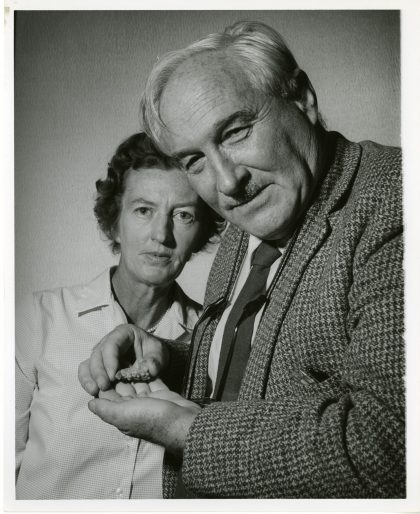

Jon also notes that the Kenyan group in Koobi Fora had an ace up their sleeve – the highly skilled indigenous Kenyan workers. These Kenyans had, before the good fortune years of Koobi Fora, worked with another member of the Leakey family, paleontologist Mary Leakey (Richard Leakey’s mother), at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania. An article on the important role that one such skilled individual, Heleson Mukiri, played in the finding of fossils in Tanzania can be found here.

There is an equally important indigenous Kenyan in the Turkana Basin expeditions. His name is Kamoya Kimeu and he was featured in a New York Times article by Donatella Lorch published in 1995.

Kamoya Kimeu made significant contributions including finding the ‘Turkana boy’, a 1.5 million old, almost complete, skeleton in 1984. Kamoya Kimeu has two fossil hominids named after him: Kamoyapithecus hamiltoni and Cercopithecoides kimeui.

Kamoya Kimeu received the National Geographic Society’s John Oliver La Gorce medal from President Ronald Reagan at a White House ceremony in October 1985.

There were other indigenous workers who found fossils and therefore made important contributions: Bernard Ngeneo, Peter Nzuve, Justus Edung, Fredrick Manthi and Cyprian Nyete.

Jon reminds us of the need to stay humble in the ‘discovery ‘ of fossils because, as he puts it, discovery is ‘relative’ and there is every chance that someone else had ‘discovered’ it before. On page 72 of his book, he writes about fossil exploration work carried out in Afar, Ethiopia as follows:

This work followed the efforts and sacrifices of others, some of whom lived to see their contributions acknowledged and rewarded, and some of whom did not. But as each new hill and stream was ‘discovered’ and mapped by newcomers, it was always under the watchful eyes of the Afar nomads, who had named these features hundreds of years before and who rightly feared that each new intruder was in some way a threat to their livelihood and future.

Jon’s message is universal. We salute all whose work has enriched our knowledge about life and its origins.

Please also see my post on the ‘discovery’ of Lake Turkana by nineteenth century explorers.